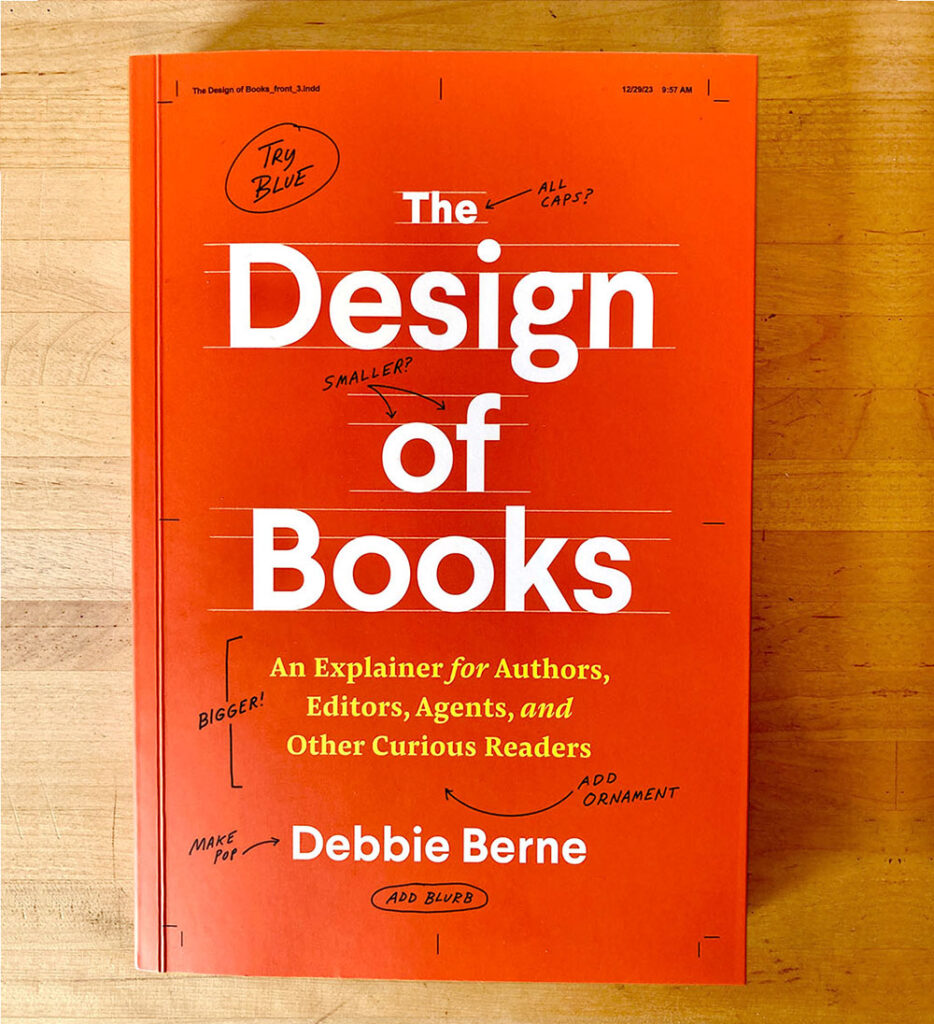

The following is excerpted from Debbie Berne’s informational guide, The Design of Books, which delves into how book design plays a crucial role in achieving publishing success and elevating a reader’s overall experience. Debbie is a seasoned book cover designer with over 20 years of experience in the industry. This is her first book.

Read our interview with Debbie from yesterday & Get your copy today!

Self-Publishing

The development of ebooks, print-on-demand technology, desktop publishing software, and the robust marketplaces for books online has made it possible for anyone to publish a book. While some authors self-publish because they cannot find a foothold in the traditional system, others opt for it right off the bat because they want the control, and higher royalty rates, that self-publishing offers.

If you’re self-publishing, you’re up against the same challenge as every other author: how to get anyone outside family and friends to read your book (or even know that it exists). Without the guidance and support of a publishing house, you have to figure out everything yourself: editing, proofreading, platforms, formats, publicity, dis-coverability, and design. The most successful independent authors assemble a support team of professionals to help them in the areas where they can’t, or don’t want to, help themselves. These authors also understand the power of a strong visual identity for their website, social media, and—the anchor—book covers. For almost all, this requires hiring professional designers to help them.

Choosing a Designer

There are a lot of designers in the world with varying skills, expertise, and price. Some work on websites, some logos, some book covers, some interiors. The first step is to hire the appropriate designer for the task. Book design is a niche field; look for a designer who knows it well. We’re discoverable through professional associations, self-publishing service providers, and “we’re really cheap”– style websites. Some publishing services keep aggregated lists of designers and design resources. When deciding whom to hire, consider the following.

Freelance Designer or Service Provider

If you have the budget, working one-on-one with a designer will give you the most control and opportunity for collaboration. If you plan to write a lot of books, in a series or not—or if you have written a lot of books and are ready to rebrand them—visual continuity will be facilitated by working with a single designer over a number of titles. There are also publishing services companies that offer a menu of design options, as well as other services, directed at the self-publishing author. This saves you the work of finding and vetting someone on your own and, ideally, ensures some structure around the process. You can also browse sites that host creative freelancers, sometimes for budget prices. You might find someone great here. But beware, these sites can be a rat’s nest of misrepresentation, soulless and generic work, and poor communication.

Visual Style

Of course. Look at designers’ portfolios, either on their personal website or on freelancer sites. Find someone whose covers you admire and who is working within your genre.

Experience

Do they have five or fifty examples of their work? Green designers can, of course, have great ideas, but you don’t need two newbies rowing the canoe. If their portfolio is small, you might check that the covers are from actual published books and not student work or design practice. An experienced designer will have a deeper knowledge of genres and categories and will be able to guide you, and the process, more successfully. (They may also have clearer boundaries, for better or worse.)

Price

Prices vary (maybe widely) and quality will usually correspond. A higher design fee will buy experience and attention. Only you know how much you have to spend, but keep in mind this truism: fast, cheap, good— pick two.

Communication

Respectful, responsive communication is an important part of any working relationship (and any relationship at all, for that matter). I only want to work with people who get back to me in a timely manner, answer with complete information, meet agreed deadlines, manage expectations, and are generally pleasant. If the person you are feeling out as a designer fails at any of these, even in the first email, look elsewhere. The process is complicated enough without that added frustration.

See the appendix for a discussion of suggested terms between an author and designer and a sample freelance design contract.

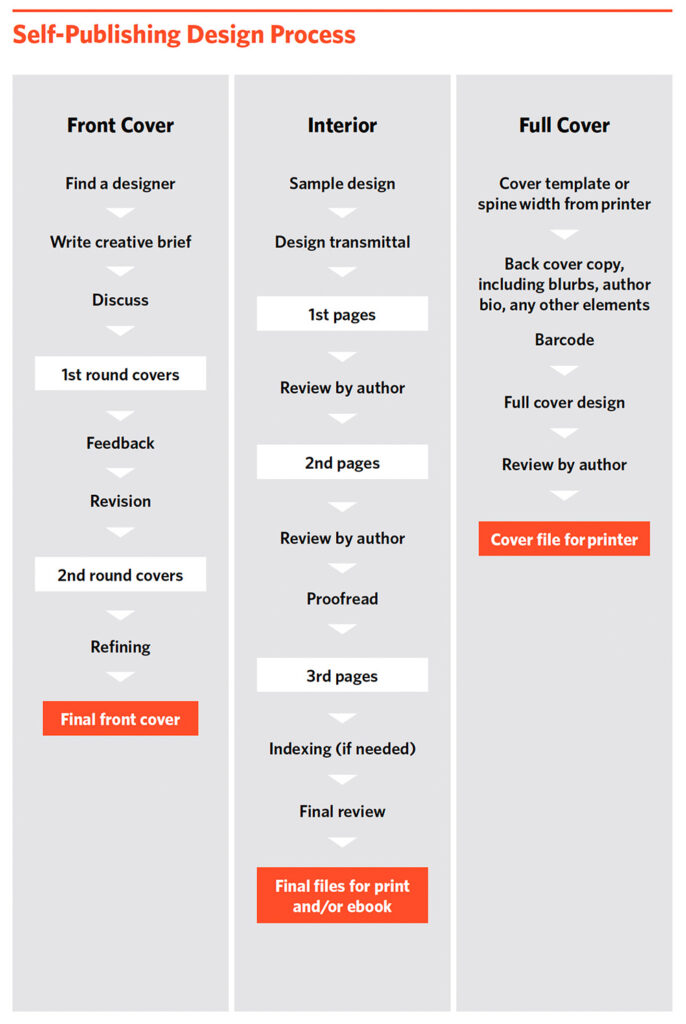

Cover Design

While I don’t think you should be your own cover designer, self-publishing does require you to be your own art director. Without the structure of a publishing house, it’s up to the author to create the circumstances that will lead to an effective process and a successful design. Working with an experienced designer will make this job easier. If you’re working one-on-one with a designer, you’ll want to hand them a cover brief and have a conversation to discuss it. A publishing services provider will most likely ask you a prescribed series of questions, many of which echo the information in the brief. Because you’re the only person that the design needs to satisfy, the rounds of feedback and iteration will be simpler than the tangle of approvals necessary through a traditional publisher. Here are my suggestions for an effective process.

The Brief

No matter what situation you’ve decided on for your cover design, write a creative brief. The brief helps you clarify what it is you want, which, in turn, will increase the chances that someone can give it to you. Return to page 66 to see the elements that belong in a cover brief.

Comps

A critical piece of the cover brief is the competitive (or comparable) research. The best way to study the other books in your genre (what will be sitting on the bookshelf, or browser screen, with yours) is to paste thumbnails of bestselling or relevant covers into a single document. There is nothing like seeing these covers, lined up together at thumbnail size, to elucidate their common traits: type style, color, kind of imagery, composition, and level of design polish. It will help you think about what you do and don’t want for your cover. If you’ve picked the right designer for your project, they may know more about this than you. If your book is hard sci-fi, look for designers who have demonstrated depth in that area. They’ll understand the conventions of the genre. If your book is memoir, same.

Imagery

Do you want photography or illustration (or neither) on your cover? Where are those images going to come from? Although you can imagine anything in the world, you may not be able to lay your hands on a suitable image. If you want original art for your cover, you may need an illustrator. (See the resources section for places to source imagery.) Full-service design sites will offer stock imagery, usually as part of the package. If you’re working one-on-one with a freelancer, the cost of images will be in addition to the design fee. And if you’re planning on providing or finding the imagery yourself, talk to the designer about it first. Some art doesn’t translate successfully for covers because it’s too busy, too literal, or leaves no space for type. All imagery in a book—and especially on the cover—must be high resolution and high quality.

Type

It’s helpful to point to type styles or fonts that you like and think would be appropriate for your cover. The designer should be familiar with what you’re pointing out and will have insight into what will or won’t be successful in this context.

Series and Brand

It’s no secret that the secret to successful self-publishing is writing a lot, often in series. If that’s your plan, communicate that to the designer. Creating a design for a one-off is a different project than creating a design that will be iterated in a series. (Creating a series look may also be more expensive than designing for a single title.) Even if you’re not planning on writing in series, tying your books together through some aspect of visual branding can be a good way for your future devoted readers to recognize your work.

Feedback

Here’s a place where the costs and benefits of not working with a publishing house are made clear. On the bright side, there’s only one person to please, and it’s you! On the other side, it’s up to you, and only you, to evaluate and respond effectively, to shepherd the not-quite-right first round toward the “chef ’s kiss” final cover. This can be a challenge, particularly if design isn’t your first language. An experienced art director might say, “The palette feels too quiet, can you make it pop more?” while you might say, “Boy, I hate that green, use purple instead.” You both may be responding to the same problem—the colors should be bolder—but the art director understands the issue (and speaks the language) while you only know that something is wrong with the colors. A traditionally published author is seeing covers that have been vetted by an experienced in-house team. Your cover is up to you.

You’ll probably be presented with three different cover ideas (or however many has been agreed on). Once you see them, it may be quite clear which direction is the strongest and which should be abandoned. Seeing something is so different from only imagining.

Use the comps. If you don’t know how to evaluate the designs, or even if you do, go back to the group of thumbnail comps you so thoughtfully gathered earlier and pop in your cover options. Comparing them to their companions, and competitors will help you see them as book covers within the context of other book covers. Which ones draw your eye? Which describe your book best? Which sit within the genre most comfortably? Do any feel too similar to other already-published books?

Write, then talk. The most useful way to relay feedback is to write it up and then talk it out. Writing out your thoughts forces you to clarify them and will give the designer a chance to absorb and consider them. But we all know what back-and-forth on email can be like. These are complex and subtle questions and worth a voice-to-voice exchange. A phone or video conversation will cover more ground, provide more context, and tend to engender trust and goodwill on both sides.

Start with why. If there are aspects you think you don’t like or may want changed, start by asking the designer why they made the choices they did. While you may wonder about another typeface for the title, there will be a host of reasons the designer picked this one. They’ll tell you if you ask: “It’s narrow and fits the space.” “It’s wide and takes up less horizontal space (so more room for the image).” “It’s sans serif and therefore less busy.” “It’s bold and reads well against the background.” “I wanted the cover to feel Gothic/modern/historic.” Now that you know, give those ideas a chance to move you forward constructively or change your perspective.

Focus on impact. Just because the designer has a reason for every choice they made doesn’t mean you have to like them all. Focus on overall impact and what you’d like to see further developed or rerouted. “Make it beachier!” “I’d like to see more of the heroine and less of the manor house.” “How can the title stand out more?” Or even, “Can it be more like this (other) cover?” If you have the benefit of a phone conversation, talk together, broadly, about how to accomplish those goals. But know that the details will be worked out in the designing and should not be overdetermined or micromanaged. I can’t say it enough times: leave the designing to the designers.

Be open. You took on the expense of hiring a professional designer for your cover. Let them bring their expertise to it. An art director doesn’t evaluate a design based on their personal preferences but on what they think is effective. You may not be a fan of red, but it might be just the right thing for this cover. Be open to the ideas the designer brings to the project and listen when they explain the logic behind their choices.

Reassess? If the first round of covers feel really off-key to you, go back to the brief. Talk through how the covers do or do not respond to genre, audience, and the original design direction. Strategize with the designer on how to right the ship. It may make sense for the next round to be quick and sketchy to be sure you are in sync before spending too much more time and effort. If the designer’s ideas aren’t headed in a direction you would have imagined, or like, it’s possible you’re a bad aesthetic match. You might consider whether it’s worth it to cut ties early, pay the kill fee, and find someone else.

Stop. Your agreement with the designer should specify the number of rounds of cover design, although some service providers offer unlimited rounds until you are satisfied (sounds like a trip through hell to me). Regardless, if you find yourself at round four or five and are still asking for changes, do yourself a favor and stop. You’re probably picking your cover to death.

The Rest of the Cover

Front cover design is always first. If your book will be published as ebook only, that’s as far as you need to go. Physical books need a spine and back cover too (jacketed books also need flaps). Full covers—back, spine, front—are created from sizing templates provided by whoever is doing the printing. To get the spine width, the printer will need to know how many pages the book has, and what paper you’ve chosen.

That means you will need to know this information, and you can’t know it until you have the final (or close-to-final) interior layout. Once you do, you should provide the spine width (or cover template) along with all the back-cover elements to the designer: the description of the book, blurbs if you’ve got them, author bio and photo, the barcode, shelving category, publishing and printing info, and art and design credits (the designer may be able to provide these).

Reprinted with permission from The Design of Books: An Explainer for Authors, Editors, Agents, and Other Curious Readers by Debbie Berne, published by the University of Chicago Press.

© 2024 by Deborah Berne. All rights reserved. Unauthorized posting, copying, or distributing of this work except as permitted under U.S. copyright law is illegal and injures the author and publisher.

The Design of Books is published by The University of Chicago Press and is available now. Get your copy today!

If you’re dying to learn more about Debbie’s incredible book, click here to read yesterday’s article: Our Q&A with Debbie herself!